|

| Elsevier (1880 colorized) |

An old man is distributing pamphlets in the street. This is very obviously counter-revolutionary political activity, so as soon as the police walk by they arrest him, and being good Communists they don't even glance at the contraband pamphlets as they seize them; their captain will know what to do.

The captain looks over the pamphlets and then storms into the interrogation room.

"These pamphlets are blank!"

The old man shrugs.

"What can I say that we do not all know already?"

This post might as well be one of those pamphlets.

Because everyone already knows that for-profit academic publishing is a racket; we are all perfectly aware that Elsevier is the Nemesis of Reason.

Or at least we ought to be. Because it is fucking obvious.

In 2017 the RELEX Group, Elsevier's parent company, reported an operating margin of 32%. Since the RELEX Group has some side hustles in data analytics, to isolate their profits from academic publishing I'll take Their science and technical division (pg. 14), which has the Elsevier brand along with such familiar names as The Lancet, Cell, and Science Direct, reported an operating margin of 37.5%.

These are the kind of margins more typically associated with criminal enterprises (for reference, Apple's operating margin was ~26%) But when you think about it, (and by think about it I mean do some critical thinking and basic arithmetic) it gets worse.

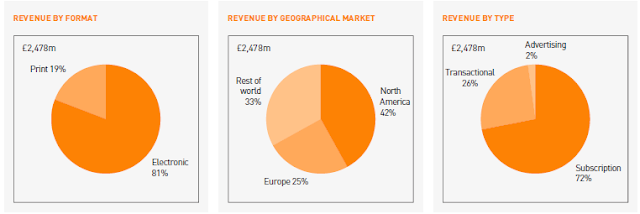

98% of their revenue is from collecting tolls as gatekeepers of information. 81% of their revenue is from electronic access. So 80% of their revenue (about ~$2.4 billion) is from gate-keeping digital content. The marginal cost of copying something digitally ins't exactly of something isn't exactly zero, but its so damn close I'm willing to call it zero.

The Racket from the Perspective of Producing the Marginal Article

An analytical distinction needs to made in analyzing the market for journal articles: are we counting the creation of the marginal article or the marginal copy of an article? That electronic copies of articles, journals, access to digital archives, etc. are overpriced is obvious (and I'll make that case in more detail later), but what about the production of a marginal article?If we think about the production of the marginal article there are clearly costs in preparing the marginal article for publication; Elsevier claims to employ 20,000 (paid) editors.

But Elsevier does not, has not, will not, and can not pay people to write the 1.6 million articles that were submitted to Elsevier in 2017, or the 430,000 that were published. Except for those who were published in the double handful (190 out of the 2500) open access journals, those people either volunteered their labor or paid for the privilege of publishing open-access in a hybrid journal.

And what Elsevier demands as compensation for making an article isn't a pittance. The fee varies between journals, but the average the price charged is around $2300.

If they didn't charging people for the privilege of adding knowledge to their hoard, how much would it cost to actually pay all those people to to produce all that content? How much would it cost to run all of Elsevier as open access?

If we are actually paying authors, at 430,000 publications, at, say 4000 words each and $1 per word (which is practically robbery for high-skill technical writing) that means it would cost Elsevier around $1.7 billion to actually, you know, pay their authors.

But of course, scholars don't write for money, (at least not directly). They write, for the love of learning, to clarify their own ideas, to qualify for tenure, to gain social status. In short, they write for intrinsic motivations, and for what the Hellenes would have called kleos, what we will call prestige.

Which is to say they are willing to write for free. Or at least, free from the perspective of their publisher.

The Elsevier makes basically all its money from people giving them things for free and then engaging in arbitrage; a business model more typically associated with solid waste management.

Is Volunteering For Suckers?

Elsevier's fees for open access give us a floor for the expected present value of (lifetime!) revenue derived from the publication of the marginal article. Since the whole operation turns a profit, it must be the case that those revenues are at least sufficient to cover the costs. So we can use these fees estimate a lower bound of those publication costs.Taking Elsevier's assessments at face-value (although I suspect the true number is lower) it would cost no more than $990 million dollars to have published everything in 2017, all 430,000 articles, as open-access.

The volunteerism of scientists and scholars in writing, submitting, and revising academic and technical publications is a precious resource, one that should probably be managed with care instead of being squeezed for profit.

But its not just individuals who are volunteering. Institutions of higher education invest sometimes staggering sums of money to enable their faculty to produce research, which is then given away to Elsevier who then charges those same universities to access the research they produced.

Frankly, I am astonished to see any institution acting so selflessly.

But it would make a lot more sense for someone to just cough up the billion dollars needed to make all this stuff, which is given away in a spirit of charitable goodwill to benefit everyone, actually available to everyone.

OK, but who would pay for that?

That is something that could be paid for entirely by a large non-profit, the federal government, or a consortium of American universities. Since part of the point of the American academy is for education to subsidize research, a $50 charge per student, across all of America's ~20 million college students, could pay for making all of Elsevier's publications in that year open access.As for archiving and hosting older publications, it'd be another $10 more; the Wikimedia Foundation makes do with an annual budget of $80 million.

In fact, I think the Wikipedian model is a good vision for the future of academic publishing. Not the "everyone can edit" part. But an open and accessible resource, maintained and sustained by a vast community of volunteer editors and contributors. After all, Elsevier's business model could basically be described as "like Wikipedia, but paywalled".

This whole analysis has been done with out estimating the social costs, social benefits, the long run drag on innovation, etc. All that could wait for another post. And I'm not trying to pick on Elsevier in particular, any for profit academic publisher would behave the same way.

But I hope alternative structures for academic publishing are possible.

It doesn't have to be this way.

[N.B. draft]

This is a fantastic article. So many scientific journals require payment to even submit new papers. It's like a magazine except all of the content is paid avertising.

ReplyDeleteWould love to see a history follow up on this. I know nothing of how elsevier and its business model came about.